ADHD Support in BC: Understanding the Gap and What Families Can Do

ADHD support in British Columbia can be difficult to access. Learn why families face long wait times and what options exist for finding help.

Learn More

The new year is a time for people to reflect on the past year and look forward to what is to come. What has passed allows us to build upon lessons learned and move toward a new vision.

What is a resolution? It is a decision to act or not act. It is typically an open-ended promise to yourself with no specific time frame for change or consideration of potential circumstances that may derail your progress. Resolutions often inspire confidence, putting you in an immediate state of motivation and belief.

Despite their long history, New Year’s resolutions have a failure rate of about 80% and are abandoned by February. Regardless, the practice of setting resolutions remains a hopeful and symbolic way to embrace change and growth.

The top three New Year’s resolutions for 2025 are “save money,” “improve physical health,” and “improve mental well-being.”

While these are admirable resolutions, they have a very low chance of success – why?

Change is hard, and it is challenging to put in effort without seeing progress. We cannot commit to a resolution if we are not ready

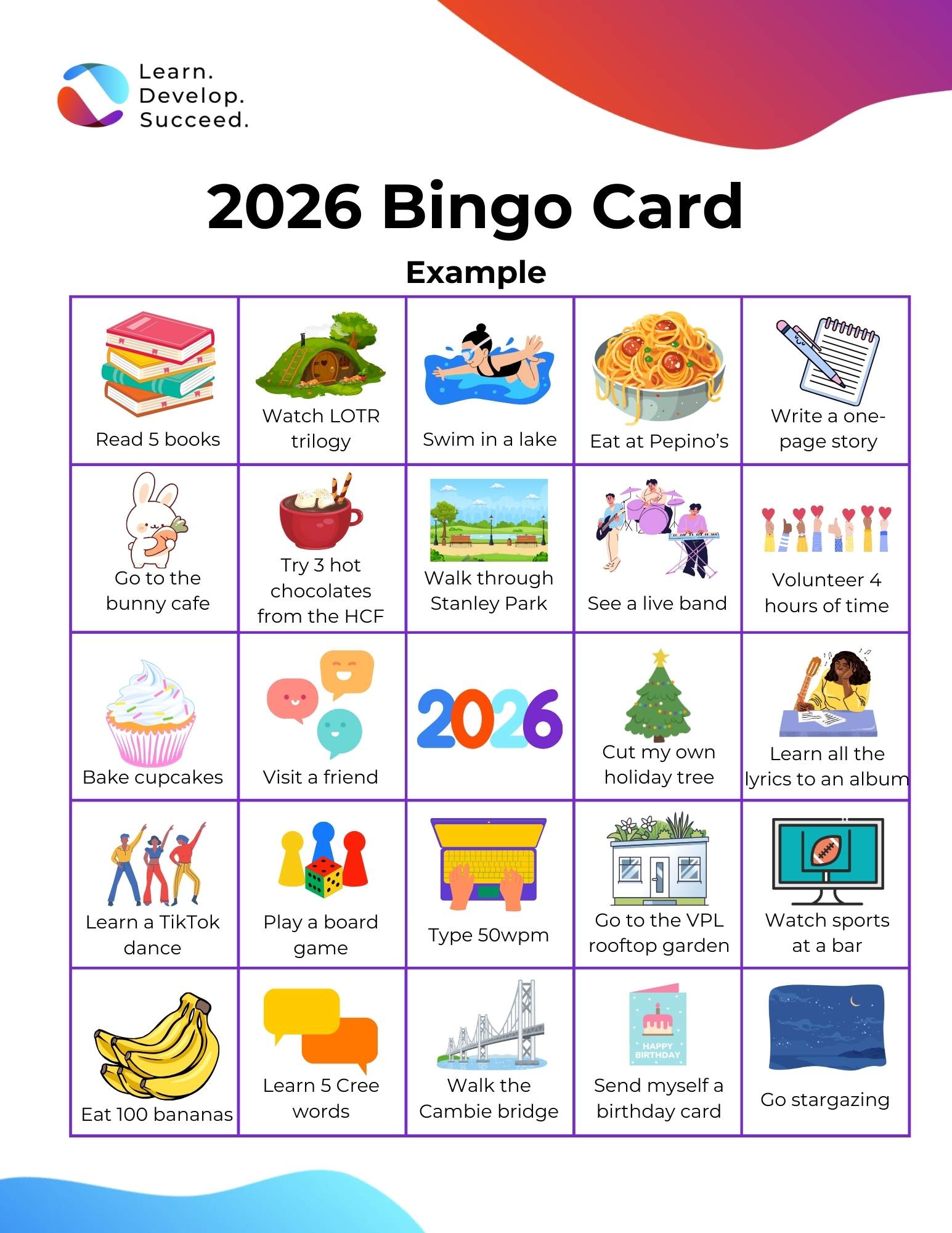

Download Bingo CardNeurodivergent individuals experience differences in sensory processing, executive functioning, emotional regulation, and information processing, all of which are necessary to successfully accomplish a resolution.

Where a resolution may require a significant change, neurodivergent individuals may be more affected by transitioning or adapting to new environments or routines. Traditional resolutions often require planning, prioritization, and effective task organization. While managing multiple sources of information and filtering out distractions, engaging in all-or-nothing thinking can lead to internal conflict and exacerbate negative emotions, ultimately impacting the outcome of a resolution.

A goal is a commitment to achieving an objective. In contrast to a resolution, goals involve a defined and targeted outcome with a clear direction of attention and effort. Typically, goals have a specific timeline and action plan, encouraging specific motivation and performance, while considering all factors that affect achievement.

When set and achieved effectively, goals can provide numerous benefits. Research indicates that individuals who set personal goals tend to experience higher levels of well-being, a greater sense of purpose, and are more likely to persist through obstacles with greater resilience. Setting goals and following through can support the development of essential executive function skills, such as time management and organization.

There are four keys to setting neuroaffirming goals that are more likely to lead to success.

Resolutions and traditional goals often overlook or disregard these key factors, and for neurodivergent individuals, ineffective goals can feel overwhelming or unattainable, leading to frustration and burnout. Neuroaffirming goals validate differences and align with unique ways of experiencing the world. They are not based on neurotypical expectations or the idea that something needs to be “fixed”—they can be about exploring, enjoying, and growing, prioritizing well-being and leaving behind the guilt of trying to meet neurotypical standards.

Before setting goals, take time to reflect on your unique strengths and challenges. Understanding your strengths will help you leverage them to achieve your goals, while recognizing your challenges will allow you to address them effectively.

You are more likely to follow through on a goal when it is rooted in what truly motivates you and takes into account your needs.

When you set a goal, reflect on the goals you have set before and think about what worked and what did not. Ask yourself whether external expectations drive the goal or if it holds personal meaning for you.

How to break it down:

Once you have a list of actions, identify a cue to trigger your brain to think about the behaviour you are aiming for. The phrase ‘out of sight, out of mind’ is particularly relevant for a neurodivergent brain.

Writing goals down in a book with a cover is less effective than writing them on sticky notes and putting them on the wall where you will see them daily.

For some, setting a specific time or schedule to work on completing the actions is beneficial. If you experience challenges with task initiation, you may want to avoid setting specific time frames or consider very small ones.

Use a timer or transition cues to help you stay on track. It can be easier to convince yourself to do something for two minutes than for 15 or 30 minutes. More often than not, you end up continuing the task; if you do not, that is okay too. It is also important to indicate how you will know you have met your goal, whether a concrete finish line or a developed habit.

It is essential to revisit your goals and mini-goals regularly to assess progress, identify any necessary adjustments, and determine whether the goal remains meaningful to you.

Life happens, things change, and your priorities might, too. Remind yourself that progress is the goal, not perfection. Incremental progress makes your brain’s reward system happy and makes you more likely to stick with it. Low effort is still effort.

– Becky Bishop, Senior Manager, Youth and Adult Programs

LDS is a community of dedicated professionals who write collaboratively. We recognize the contribution of unnamed team members for their wisdom and input.

Receive our bi-weekly Arise newseltter which includes resources, updates, stories, events, and more.